-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

David M.. Morens, Jeffery K. Taubenberger, Anthony S. Fauci, Predominant Role of Bacterial Pneumonia as a Cause of Death in Pandemic Influenza: Implications for Pandemic Influenza Preparedness, The Journal of Infectious Diseases, Volume 198, Issue 7, 1 October 2008, Pages 962–970, https://doi.org/10.1086/591708

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

Background. Despite the availability of published data on 4 pandemics that have occurred over the past 120 years, there is little modern information on the causes of death associated with influenza pandemics.

Methods. We examined relevant information from the most recent influenza pandemic that occurred during the era prior to the use of antibiotics, the 1918–1919 “Spanish flu”; pandemic. We examined lung tissue sections obtained during 58 autopsies and reviewed pathologic and bacteriologic data from 109 published autopsy series that described 8398 individual autopsy investigations.

Results. The postmortem samples we examined from people who died of influenza during 1918–1919 uniformly exhibited severe changes indicative of bacterial pneumonia. Bacteriologic and histopathologic results from published autopsy series clearly and consistently implicated secondary bacterial pneumonia caused by common upper respiratory-tract bacteria in most influenza fatalities.

Conclusions. The majority of deaths in the 1918–1919 influenza pandemic likely resulted directly from secondary bacterial pneumonia caused by common upper respiratory-tract bacteria. Less substantial data from the subsequent 1957 and 1968 pandemics are consistent with these findings. If severe pandemic influenza is largely a problem of viral-bacterial copathogenesis, pandemic planning needs to go beyond addressing the viral cause alone (e.g., influenza vaccines and antiviral drugs). Prevention, diagnosis, prophylaxis, and treatment of secondary bacterial pneumonia, as well as stockpiling of antibiotics and bacterial vaccines, should also be high priorities for pandemic planning.

“If grippe condemns, the secondary infections execute”; [1, p. 448].

—Louis Cruveilhier, 1919

Influenza pandemic preparedness strategies in the United States [2] assume 3 levels of potential severity corresponding to the 20th century pandemics of H1N1 “Spanish flu”; (1918–1919), H2N2 “Asian flu”; (1957–1958), and H3N2 “Hong Kong flu”; (1968–1969), which were responsible for an estimated 675,000 [3], 86,000 [4], and 56,300 [5] excess deaths in the United States, respectively. Extrapolation from 1918–1919 pandemic data to the current population and age profile has led United States government officials to plan for more than 1.9 million excess deaths during a severe pandemic [2].

An important question related to pandemic preparedness remains unanswered: what killed people during the 1918–1919 pandemic and subsequent influenza pandemics? In the present study, we have examined recut tissue specimens obtained during autopsy from 58 influenza victims in 1918–1919, and have reviewed epidemiologic, pathologic, and microbiologic data from published reports for 8398 postmortem examinations bearing on this question. Wehave also reviewed relevant information, accumulated over 9 decades, related to the circulation of descendants of the 1918 virus. With the recent reconstruction of the 1918 pandemic influenza virus, investigators have begun to examine why it was so highly fatal [6, 7]. Based on contemporary and modern evidence, we conclude here that influenza A virus infection in conjunction with bacterial infection led to most of the deaths during the 1918–1919 pandemic.

Methods

Examination of tissue specimens from 1918–1919 influenza fatalities. We reviewed hematoxylin and eosin-stained slides recut from blocks of lung tissue obtained during autopsy from 58 influenza fatalities in 1918–1919. These materials, sent during the pandemic from various United States military bases to the National Tissue Repository of the Armed Forces Institute of Pathology [8–10], represent all known influenza cases from this collection for which lung tissue is available.

Pathology and bacteriology research records from the 1918–1919 influenza pandemic. We reviewed the late 19th- and early 20th-century literature on gross and microscopic influenza pathology and bacteriology, including evidence from 1918–1919 autopsy series with postmortem cultures of lung tissue, blood samples (usually heart blood), pleural fluid, and samples from other compartments. In an effort to obtain all publications possibly reporting influenza pathology and/or bacteriology in 1918–1919, we searched major bibliographic sources [e.g., 11–17] for papers in all languages and tables of contents of major journals in English, German, and French; in addition, we searched all of the papers we identified for additional citations. From more than 2000 such publications, we carefully examined the 1539 reports that contained human pathologic and/or bacteriologic findings (the full bibliographic list available at http://www3.niaid.nih.gov/topics/Flu/1918/bibliography.htm), 109 of which provided useful bacteriologic information derived from 173 autopsy series. These series reported 8398 individual autopsy investigations undertaken in 15 countries, which can be characterized as follows: 96 postmortem lung tissue culture series, 42 blood culture series, and 35 pleural fluid culture series. When they were published as parts of an autopsy series, we included in our analyses antemortem cultures of blood and pleural fluid samples, which were mostly obtained during the terminal stages of illness. A priori, we stratified data by military and civilian populations (see Discussion), and by the quality of lung tissue culture results, considering to be of “higher quality”; the 68 autopsy series with lung tissue culture results that reported, for all autopsies, both the presence and absence of negative culture results and the bacterial components of mixed culture results.

Results

Background epidemiologic data on influenza mortality rates in 1918–1919. Although death certificates listing cardiac and other chronic causes of death increased in number during the time frame of the 1918–1919 pandemic [18], for all age groups death was predominantly associated with pneumonia and related pulmonary complications [13, 14, 18–20]. The pandemic caused a “W-shaped”; age-specific mortality curve, which exhibited peaks in infancy, between about 20–40 years of age, and in elderly individuals [3, 21]. In all age groups younger than ~65 years, the influenza mortality rate was elevated beyond what would have been expected on the basis of data from the previous pandemic of “Russian influenza”; (1889–1893) [3, 22, 23]. The increased fatality rate in the 3 high-risk age groups was predominantly due to the increased frequency of bronchopneumonia, not to increased incidence of influenza or an increased bronchopneumonia case-fatality rate [19]. Because few autopsy reports and, to our knowledge, no autopsy series addressed conditions other than predominantly pulmonary complications, nonpulmonary causes of death are not considered here.

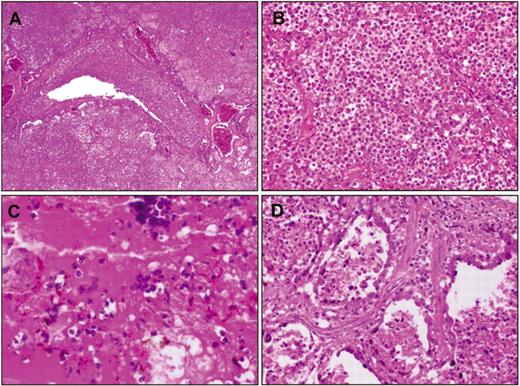

Histologic examination of lung tissue from 1918 victims. The examination of recut lung tissue sections from 1918–1919 influenza case material revealed, in virtually all cases, compelling histologic evidence of severe acute bacterial pneumonia, either as the predominant pathology or in conjunction with underlying pathologic features now believed to be associated with influenza virus infection [10, 24] (figure 1). The latter include necrosis and desquamation of the respiratory epithelium of the tracheobronchial and bronchiolar tree, dilation of alveolar ducts, hyaline membranes, and evidence of bronchial and/or bronchiolar epithelial repair [25, 26]. The majority of the cases examined demonstrated asynchronous histopathological changes, in which the various stages of development of the infectious process, from early bronchiolar changes to severe bacterial parenchymal destruction, were noted in focal areas. The histologic spectrum observed in the cases corresponded to the characteristic pathology of bacterial pneumonia, including bronchopneumonia [10,24–33]: lobar consolidation with pulmonary infiltration by neutrophils in pneumococcal pneumonia; a bronchopneumonic pattern, edema, and pleural effusions in streptococcal and sometimes in pneumococcal pneumonia; and in staphylococcal pneumonia, multiple small abscesses with a marked neutrophilic infiltration in airways and alveoli [27]. Bacteria were commonly observed in the sections, often in massive numbers.

Examples of hematoxylin and eosin-stained postmortem lung sections from 4 victims of the 1918–1919 influenza pandemic (see text). A, Typical picture of severe, widespread bacterial bronchopneumonia with transmural infiltration of neutrophils in a bronchiole and with neutrophils filling the airspaces of surrounding alveoli (original magnification, 40×). B, Massive infiltration of neutrophils in the airspaces of alveoli associated with bacterial bronchopneumonia as in A (original magnification, 200×). C, Bronchopneumonia with intra-alveolar edema and hemorrhage. Numerous bacteria are visible both in the edema fluid and in the cytoplasm of macrophages (original magnification, 400×). D, Bronchopneumonia with evidence of pulmonary repair. The alveolar epithelium is hyperplastic; interstitial fibrosis is seen between alveoli (original magnification, 200×).

Published pathologic and/or bacteriologic findings from the 1918–1919 influenza pandemic. Although the cause of influenza was disputed in 1918, there was almost universal agreement among experts [e.g., 20, 27–33] that deaths were virtually never caused by the unidentified etiologic agent itself, but resulted directly from severe secondary pneumonia caused by well-known bacterial “pneumopathogens”; that colonized the upper respiratory tract (predominantly pneumococci, streptococci, and staphylococci). Without this secondary bacterial pneumonia, experts generally believed that most patients would have recovered [20]. In type, pattern, and case-fatality rate, influenza-associated bacterial pneumonia was typical of pneumonia that was endemic during periods when influenza was not prevalent [25, 28, 33, 34]. As described above, in cases for which a single lung pathogen was recovered from culture, the anatomical-pathological type of the pneumonia usually corresponded to what was expected. Bacteria were commonly observed in cases of pneumonia caused by each of these pathogens. Such findings reflect the characteristic pathology of bacterial pneumonia [10, 25, 27].

Surprising aspects of 1918–1919 influenza-associated pneumonia fatalities included the following: (1) the high incidence of secondary pneumonia associated with standard bacterial pneumopathogens; (2) the frequency of pneumonia caused by both mixed pneumopathogens (particularly pneumococci and streptococci) and by other mixed upper respiratory-tract bacteria; (3) the aggressiveness of bacterial invasion of the lung, often resulting in “phenomenal”; [30] numbers of bacteria and poly-morphonuclear neutrophils, as well as extensive necrosis, vasculitis, and hemorrhage [20, 32, 33]; and (4) the predominance of bronchopneumonia and lobular pneumonia, as opposed to lobar pneumonia, consistent with diffuse predisposing bronchiolar damage [27–33].

Contemporary views of the natural history of severe influenza during the 1918–1919 influenza pandemic. By examining influenza autopsy materials from a range of patients in different stages of disease, pathologists in 1918–1919 identified the primary lesion in early severe influenza-associated pneumonia as desquamative tracheobronchitis and bronchiolitis extending diffusely over all or much of the pulmonary tree to the alveolar ducts and alveoli, associated with sloughing of bronchiolar epithelial cells to the basal layer, hyaline membrane formation in alveolar ducts and alveoli, and ductal dilation [20, 24, 27, 29–33].

Primary “panbronchitis”; [35] was thought to reflect rapidly spreading epithelial cytolytic infection of the entire bronchial tree [32, 35, 36]; this was thought to have led to the secondary spread of enormous numbers of bacteria along the denuded bronchial epithelium to every part of the bronchial tree, following which focal bronchiolar infections broke through into the lung parenchyma. Secondary bacterial invasion and zones of vasculitis, capillary thrombosis, and necrosis surrounding areas of bronchiolar damage were seen in severe cases. As was true for the 58 autopsy cases we reviewed (see above), published autopsies for victims of the 1918–1919 pandemic generally showed histopathological asynchrony [20]. Repair, represented by early epithelial regeneration, capillary repair, and occasionally by fibrosis, was commonly seen in tissues sections from even the most fulminant fatal cases [20, 27, 32]. Among the ⩾60% of individuals who survived such severe pneumonia, severe chronic pulmonary damage was apparently uncommon [37, 38].

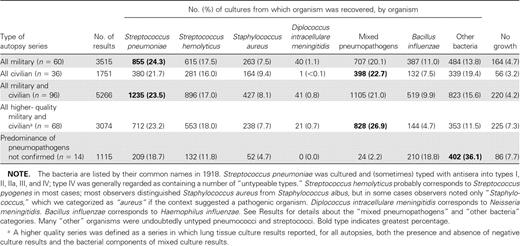

Bacteriologic studies in autopsy series during the 1918–1919 influenza pandemic. Negative lung culture results were uncommon in the 96 identified military and civilian autopsy series, which examined 5266 subjects (4.2% of results overall) (table 1; full bibliographic list available at http://www3.niaid.nih.gov/topics/Flu/1918/bibliography.htm). In the 68 higher-quality autopsy series, in which the possibility of unreported negative cultures could be excluded, 92.7% of autopsy lung cultures were positive for ⩾1 bacterium (table 1). Of these 96 series, 82 reported pneumopathogens in ⩾50% of lungs examined, either alone or in mixed culture results that included other bacteria (table 1). Outbreaks of meningococcal pneumonia complicating influenza also were documented [39]. Despite higher military case-fatality rates, the differences in the frequency with which specific bacteria were isolated from lung tissue cultures (table 1) and from culture of blood and pleural or empyema fluids (data not shown) were minimal. Many of the series were methodologically rigorous: in one study of approximately 9000 subjects who were followed from clinical presentation with influenza to resolution or autopsy [40], researchers obtained, with sterile technique, cultures of either pneumococci or streptococci from 164 of 167 lung tissue samples. There were 89 pure cultures of pneumococci; 19 cultures from which only streptococci were recovered; 34 that yielded mixtures of pneumococci and/or streptococci; 22 that yielded a mixture of pneumococci, streptococci, and other organisms (prominently pneumococci and nonhemolytic streptococci); and 3 that yielded nonhemolytic streptococci alone. There were no negative lung culture results.

Examples of hematoxylin and eosin-stained postmortem lung sections from 4 victims of the 1918–1919 influenza pandemic (see text). A, Typical picture of severe, widespread bacterial bronchopneumonia with transmural infiltration of neutrophils in a bronchiole and with neutrophils filling the airspaces of surrounding alveoli (original magnification, 40×). B, Massive infiltration of neutrophils in the airspaces of alveoli associated with bacterial bronchopneumonia as in A (original magnification, 200×). C, Bronchopneumonia with intra-alveolar edema and hemorrhage. Numerous bacteria are visible both in the edema fluid and in the cytoplasm of macrophages (original magnification, 400×). D, Bronchopneumonia with evidence of pulmonary repair. The alveolar epithelium is hyperplastic; interstitial fibrosis is seen between alveoli (original magnification, 200×).

In the 14 of 96 autopsy series that did not report the predominance of lung pneumopathogens [29, 36, 41–53], pneumopathogens accounted collectively for 37.4% of pneumonia deaths. The rest of the deaths were associated collectively with either culture of nonpneumopathogenic “other bacteria,”; such as nonhemolytic and viridans streptococci, “green-producing streptococci”; [54], probably largely corresponding to α-hemolytic streptococci, uncharacterized diplostreptococci, Micrococcus (Moraxella) catarrhalis, Bacillus (Escherichia) coli, Klebsiella species, and complex mixed bacteria (36.1% of cultures). Cultures also yielded Bacillus influenzae (18.8%) and no bacterial growth (7.7%). These findings reflect rates of bacterial isolation similar to those of the series that reported the predominance of pneumopathogens (above and table 1), but with higher isolation rates for “other bacteria”; offsetting the lower isolation rates for pneumococci, streptococci and staphylococci. It is noteworthy that pneumococcal typing antisera were unavailable in 11 of these 14 studies, and that many of the cultured “other”; bacteria were reported as “gram-positive diplococci,”; “streptococci,”; or “diplostreptococci”; (data not shown), consistent with the possibility that in this early era of bacterial typing, some of the unidentified organisms in the culture may have been pneumopathogens.

The predominant coinfecting microorganism in lung tissue cultures containing ⩾1 pneumopathogen was Bacillus influenzae (largely corresponding to the modern Hemophilus influenzae), an upper respiratory-tract organism not commonly found in pure culture of samples from any anatomical compartment [20, 36, 55]. Bacillus influenzae tended to appear early in symptomatic influenza in association with diffuse bronchitis and/or bronchiolitis, sometimes infiltrating the bronchiolar submucosa [35]; it caused seroconversion [56] and was then typically replaced by other secondary organisms.

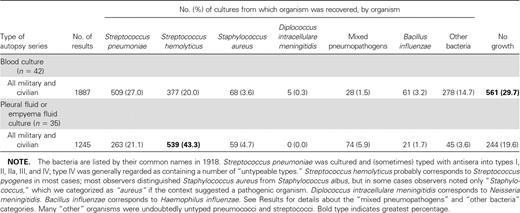

Cultures of blood samples in 30 military and 12 civilian series, which examined a total of 1887 subjects (table 2), had positive results in 70.3% of cases and typically contained either pneumococci or streptococci in pure culture. Cultures of pleural or empyema fluid, reported in 23 military and 12 civilian series examining a total of 1245 subjects (table 2), revealed either streptococci or pneumococci as the most commonly recovered organism in all but 7 series: in 4 series mixed pneumopathogens predominated, and in 3 series Staphylococcus aureus predominated. Most subjects with positive culture results in the blood and pleural or empyema fluid series also had ⩾1 pneumopathogen cultured in samples from the lungs (data not shown).

Bacterial culture results in autopsy series involving 96 postmortem cultures of lung tissue from victims of the 1918–1919 influenza pandemic.

Of 2007 pneumococcal isolates, 874 (43.5%) were serotyped by agglutination. Type I was isolated from 124 (14.2%) of 874 subjects; type II from 163 (18.6%); type IIa from 26 (3.0%); type III from 184 (21.1%); and type IV, a category containing diverse and, at the time, untypeable organisms, from 377 (43.1%).

Pathologic and bacteriologic information obtained from later pandemic and seasonal influenza cases. The viruses that caused the 1957 and 1968 pandemics were descendants of the 1918 virus in which 3 (the 1957 virus) or 2 (the 1968 virus) new avian gene segments had been acquired by reassortment [21]. Although lower pathogenicity resulted in far fewer deaths, hence fewer autopsies, most 1957–1958 deaths were attributable to secondary bacterial pneumonia, as had been the case in 1918. Staphylococcus aureus, a relatively minor cause of the 1918 fatalities, was predominant in the culture results from 1957–1958 [21, 57–61], and negative lung tissue cultures were more common, possibly as a result of the widespread administration of antibiotics [57, 58, 61]. The few relevant data from the 1968–1969 pandemic (see below) are consistent with information from the earlier 20th-century pandemics. Human tracheobronchial biopsy studies performed since the 1957–1958 epidemic characterized the natural history of influenza virus infection as featuring rapid (within 24 h) development of bronchial epithelial necrosis, preservation of the basal layer, limited inflammatory response, and evidence of prompt repair [62], consistent with the observations of pathologists in 1918–1919.

Discussion

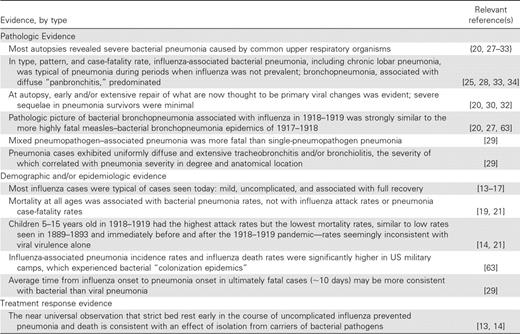

In the most recent influenza pandemic that did not involve the use of antibiotics to suppress bacteria (the 1918–1919 pandemic), histological and bacteriologic evidence suggests that the vast majority of influenza deaths resulted from secondary bacterial pneumonia. Compelling evidence for this conclusion includes the examination of 58 recut and restained autopsy specimens that showed changes fully consistent with classical descriptions of extensive bacterial pneumonia [25], culture results from numerous international autopsy series, and consistent epidemiologic and clinical findings (table 3).

Summary of evidence from the 1918–1919 influenza pandemic consistent with the conclusion that bacterial pneumonia, rather than primary viral pneumonia, was the cause of most deaths.

Between 1890 and 1950, most observers believed fatal influenza to be a polymicrobial infection in which an inciting agent of low pathogenicity (either a bacterium such as Bacillus influenzae or a “filter passing agent”;–most of which have now been identified as viruses) acted synergistically with known pneumopathogenic bacteria [13, 14, 20, 33, 64–66]. This view was dramatically supported in 1917–1918 by the measles epidemics in US Army training camps, in which most deaths resulted from streptococcal pneumonia or, less commonly, pneumococcal pneumonia [20, 30, 32]. The pneumonia deaths during the influenza pandemic in 1918 proved so highly similar, pathologically, to the then-recent pneumonia deaths from the measles epidemics that noted experts considered them to be the result of one newly emerging disease: epidemic bacterial pneumonia precipitated by prevalent respiratory tract agents [20, 33, 63].

The question of whether the pathogenesis of severe influenza-associated pneumonia was primarily viral (i.e., assumed to be an unknown etiologic agent in 1918) or a combination of viral and bacterial agents was carefully considered by pathologists in 1918–1919, without definitive resolution [26, 33]. The issue was addressed anew in the early 1930s when Shope published a series of experimental studies that involved the just-discovered swine influenza A virus: severe disease in an animal model resulted only when the virus and Hemophilus influenzae suis were administered together [67]. In 1935, Brightman studied combined human influenza and streptococcal infection in a ferret intranasal inoculation model. Even though neither agent was pathogenic when administered alone, they were highly fatal in combination [68]. In rhesus monkeys, human influenza viruses given intranasally were not pathogenic, but could be made so by nasopharyngeal instillation of otherwise nonpathogenic bacteria [69]. During the 1940s, additional studies in ferrets, mice, and rats established that the influenza virus in combination with any of several pneumopathic bacteria acted synergistically to produce either a higher incidence of disease, a higher death rate, or a shortened time to death [70–73]; these effects could be mitigated or eliminated if antibiotics were given shortly after establishment of combined infection [73]. More recent data suggest that influenza vaccination may prevent bacterial disease [74].

As reviewed recently by McCullers [75], a body of experimental research during the last 3 decades has identified possible mechanisms by which coinfection with the influenza virus and bacteria might affect pathogenicity. These include viral neuraminidase (NA)-induced exposure of bacterial adherence receptors; bacterial NA-induced upregulation of influenza infection; interleukin 10-induced susceptibility to pneumococci and possibly staphylococci [76]; interferon type 1 effects [77]; viral PB1-F2 effects, the proaptotic and mitochondriopathic effects of which are correlated with enhanced bacterial infection [78]; and virus-induced desensitization to bacterial Toll-like receptor ligands [79].

We believe that the weight of 90 years of evidence (table 3), including the exceptional but largely forgotten work of an earlier generation of pathologists, indicates that the vast majority of pulmonary deaths from pandemic influenza viruses have resulted from poorly understood interactions between the infecting virus and secondary infections due to bacteria that colonize the upper respiratory tract. The data are consistent with a natural history in which the virus, highly cytopathic to bronchial and bronchiolar epithelial cells, extends rapidly and diffusely down the respiratory tree, damages the epithelium sufficiently to break down the mucociliary barrier to bacterial spread, and if able to gain access to the distal respiratory tree–perhaps on the basis of receptor affinity [80]–creates both a direct pathway for secondary bacterial spread and an environment (cell necrosis and proteinaceous edema fluid) favorable to bacterial growth. It remains unresolved whether cocolonizing, nonpneumopathic upper respiratory-tract organisms such as Bacillus (Hemophilus) influenzae play an ancillary role, or are merely innocent bystanders. It is uncertain why Hemophilus influenzae was much less prominent in 1957–1958 and thereafter, but this phenomenon may relate to antibiotic use and conceivably, in recent years, to Hemophilus influenzae b vaccination of children.

The extraordinary severity of the 1918 pandemic remains unexplained. That the causes of death included so many different bacteria, alone or in complex combinations, argues against specific virulent bacterial clones. The pathologic and bacteriologic data appear consistent with copathogenic properties of the virus itself, perhaps related to viral growth, facility of cell-to-cell spread, cell tropism, or interference with or induction of immune responses. Certain observers believed that cotransmission of the influenza agent and of pneumopathogenic bacteria was responsible for many severe and fatal cases, especially during the October-November 1918 peak of mortality and case-fatality rates [81]. We speculate that any influenza virus with an enhanced capacity to spread to and damage bronchial and/or bronchiolar epithelial cells, even in the presence of an intact rapid reparative response, could precipitate the appearance of severe and potentially fatal bacterial pneumonia due to prevalent upper respiratory-tract bacteria.

In the modern era, the widespread use of antibiotics and the establishment of life-prolonging intensive care unit treatment make it more difficult than it was in 1918 to document the importance of bacterial lung infection for influenza-related mortality. Influenza-associated pneumonia patterns may now be influenced by the administration of pneumococcus, Hemophilus influenzae b, and meningococcus vaccine, and cases have tended to occur in elderly individuals, who rarely undergo autopsy. The 1968 influenza pandemic was mild, and autopsy studies were uncommon [21]. Fatal cases of influenza-associated viral pneumonia that are considered to be “primary”; (i.e., with little or no bacterial growth) continue to be identified [82, 83]; however, their incidence appears to be low, even in pandemic peaks. The issue of the pathogenesis of fatal influenza-associated pneumonia remains important; the fact that even severe, virus-induced tissue damage is normally followed by rapid and extensive repair [20, 26] suggests that early and aggressive treatment, including antibiotics and intensive care, could save most patients [84, 85] and also underscores the importance of prevention and prophylaxis.

The 1918 pandemic and subsequent pandemics differed with respect to the spectrum and extent of secondary bacterial pneumonia (e.g., the switch in prevalence during the antibiotic era to predominantly staphylococcal secondary pneumonia, as opposed to streptococcal, pneumococcal, and mixed secondary pneumonia; and the greatly decreased involvement of Bacillus [Hemophilus] influenzae), suggesting that additional factors affect the level of influenza morbidity and mortality. These might include the use of antibiotics and antiviral agents, the rate of influenza vaccination and bacterial vaccination, and demographic and social factors. The aging population in the United States, the increasing number of persons living in nursing home facilities, and the number of persons who are immunosuppressed or affected by cardiac disease, renal disease, and/or diabetes mellitus all represent potential factors that might change the profile of morbidity and mortality during a future pandemic. for example, elderly persons in nursing homes are at risk for pneumonia caused by enteric organisms and sometimes by drug-resistant nosocomial organisms. The spread of bacteria such as methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus and highly pathogenic clones of Streptococcus pyogenes pose more general risks [86].

The viral etiology of and timing of the next influenza pandemic cannot be predicted [87]. If, as some fear, a future pandemic is caused by a derivative of the current highly pathogenic avian H5N1 virus, lessons from previous pandemics may not be strictly applicable. Although histopathologic information concerning current human H5N1 infections is sparse [10], its pathogenic mechanisms may be atypical because the virus is poorly adapted to humans [88] and because, in certain experimental animal models [e.g., 89], some strains have induced severe pathology that differs from the findings associated with circulating human influenza viruses (which, in these models, cause disease resembling self-limited seasonal influenza in humans [90]). However, if an H5N1 virus were to fully adapt to humans, the clinicopathologic spectrum of associated disease could become more like that of previous pandemics.

If the next pandemic is caused by a human-adapted virus similar to those recognized since 1918, we believe the infection is likely to behave as it has in past pandemics, precipitating severe disease associated with prevalent colonizing bacteria. Recent reviews have discussed the importance of new and improved influenza antiviral drugs and influenza vaccines in controlling a pandemic [84, 91, 92]. The present work leads us to conclude that in addition to these critical efforts, prevention, diagnosis, prophylaxis, and treatment of bacterial pneumonia, as well as the stockpiling of antibiotics and bacterial vaccines [84, 85, 93], should be among the highest priorities in pandemic planning. We are encouraged that such considerations are already being discussed and implemented by the agencies and individuals responsible for such plans [94, 95].

Acknowledgments

We thank Betty Murgolo and the staff of the National Institutes of Health (NIH) Library, for extensive research efforts in locating publications, and the staff of the History of Medicine Division, National Library of Medicine, NIH, for additional library research support. Wealso thank Cristina Cassetti, PhD, and Andrea Scollard, DDS, PhD for translation of Italian language and Portuguese language papers, respectively; Hillery A. Harvey, PhD, for scientific assistance; and Gregory K. Folkers, MS, MPH, for helpful discussion and editorial assistance. John J. McGowan, PhD, and the staff of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID) Pandemic Influenza Digital Archives project provided substantial assistance in organizing and indexing historical manuscripts.

References

Potential conflicts of interest: none reported.

Financial support: Intramural Research Program of the National Institutes of Health; National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases.

Presented in part: 2006 Annual Meeting of the American Epidemiological Society, Berkeley, California, 30 March, 2006; and 2007 Annual Meeting of the American Epidemiological Society, Boston, Massachusetts, 26 March 2007.